My sons in Zambia

Malama is going to go to the Copperbelt next month to arrange a visit to a mine. The visit will be part of our Zamscot tour in July, when four members of Coisir Og Dhail Riata – the Mid Argyll Junior Gaelic Choir – and six young musicians from the Isle of Barra will share traditional music with members of the Mthunzi Culture Group and learn about traditional industries in Zambia.

I spent Christmas with some of the young people from Mthunzi. We talked a lot about politics and who was to blame for some of the copper mines closing. It's a topic close to the hearts of young Zambians who have spent some of their lives scrubbing a living on the streets of Lusaka. My 'son' Jack's dad was a manager in a copper mine. Both parents died when he was about 12 or 13 and he hid under the seats on a train from Ndola to get to Lusaka. He washed cars and hung out under railway bridges until he was picked up by carers from the Mthunzi Centre, which has been looking after 65 former street children since the start of this century. Jack is 22 now and in Grade 11 at school. My other 'son', Charles, is also 22 and has just finished school. He's waiting for his exam results so that he can apply for a multimedia course. Like all the Mthunzi boys, they have great ambitions to be 'the future of Zambia'; to change things for the better.

In the days of Zambia's first president, Kenneth Kaunda, the price of copper slumped. Plastic was the thing and the one commodity that the colonialists had developed in Zambia (formerly Northern Rhodesia) was rendered useless. More recently, copper has come into its own again – mobile phones, computers, cars, cables all use the stuff and foreign companies have snapped up the once redundant mines on the understanding that they'll get favourable tax deals.

The Mthunzi boys are sceptical about the politicians now leading their country. Despite a move towards free enterprise, despite copper's resurgence, Zambia is still the ninth poorest country in the world. In the decade I've been closely involved with these young people, their life expectancy has fallen from 48 to 37 years. In the UK we are worried about the falling value of pensions, savings, interest rates. I've got a bus pass and I could still outlive some of the youngsters at Mthunzi.

I was at Mthunzi to plan this forthcoming Zamscot exchange. Their culture group spent last August here in Argyll, Barra and Troon, made a CD with the young women from the Gaelic Choir (singing Gaelic songs) and learned about fishing and farming and the stuff of the western fringe of Scotland. In advance of the return match, our young musicians are learning some songs about farming and mining in Nyanja, Bemba and Tonga, just three of Zambian's 73 traditional languages.

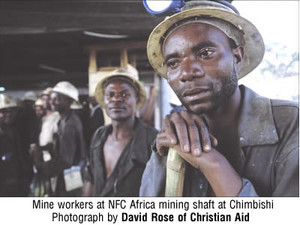

Will Malama, who runs the Mthunzi Centre, find a functioning mine for us to visit? And if some are closing, is it all to do with the 'Downturn', or to political mismanagement? A significant report produced by the Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund (SCIAF), Christian Aid and Action for Southern Africa (ACTSA) released at the end of last year showed that Zambians were reaping few of the benefits of the resurgence of copper and many were suffering from poor working conditions. The report focused on Zambia's largest copper mining company, Konkola Copper Mines (KCM). A company called Vedanta Resources has a 51% share in KCM. It's based in London and when the report was written, it had several London and Edinburgh-based investors, including Barclays Bank, HSBC, Standard Life and HBOS. These investors were asked to re-think their role in operations that offered low pay, poor health and safety conditions, and little investment in the Zambian economy, despite the tax concessions. Some have complied with that request.

The outcome of the campaign inspired by this report is an announcement by the Zambian government that new measures are to be taken to get the mining companies to pay an additional £207 million in taxes. This money will be used to 'implement vital programmes in health and education', according to the Zambian government. Is it going to benefit 'my' boys? Is Jack, whose dad tried desperately to keep his family on a copper mine pittance, going to get government help to go to college to fulfil his dreams? Will Robert eventually get his tonsils removed (he's been in hospital twice and sent home because there was no-one to do the operation)? And will young Joseph, third in Lusaka District in his last exams, fly in the academic firmament where he belongs?

If I'd read the small print, I'd have avoided putting some of my savings in Standard Life. If the West had warned the Zambian government about tax concessions, the whole scene could have been different. After all, in the 1980s, Scotland developed an art form of offering concessions to foreign companies that were to revolutionise our own ailing economy, then watching them scarper as the tax deals ended.

There was a young volunteer worker sitting near me on the plane coming home. She was telling her neighbour that 'they' needed economists not accountants. I'd feed economists to the crocodiles. Metaphorically speaking, of course.

© The Scottish Review