A STRATEGIC FACTOR IN CLAIMING AFRICA'S FUTURE

Introduction

In the last two decades or so, many African countries have been preoccupied with various forms of structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) and economic reforms, with the goading of the Bretton Woods institutions (the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank). In many instances, this preoccupation was so single-minded that it almost amounted to the creed of seeking first the economic and financial kingdom and all else would follow. This exercise of balancing the macroeconomic books– the internal balance of the budget and the external balance of trade–had mixed results in the economic and financial sphere[i] and disastrous consequences in the human development and social sphere. It led to deepening unemployment and diminished provision of social services: water, education, health services, infrastructure, etc.Many individuals, institutions and non-governmental organizations questioned the worthiness of policies that result in such adverse outcomes as joblessness and poverty, and called for adjustment with a human face and the instituting of policies such as social safety nets to meet the basic needs of the vulnerable, the marginalized and the disadvantaged.[ii]

By this time, a lot of damage had been done. First, the balance of power had been tilted in favour of government treasuries and central banks. Second, social development had been relegated to the background and had come back as an afterthought. Many feel it is central and should be up-front; not seen as a palliative, but as an essential capacity for development.[iii] A major component of that scheme of things is the development of human resources.

The Importance of Human Resources

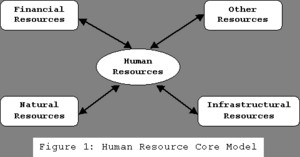

According to Julian Simon, people are “the ultimate resource”[iv] because of ingenuity which comes from the power of the human mind. It is the human resource that plans and takes risk, organizes and manages other resources, and invents and innovates. This is the production-good view of human resources, and underpins the human capital perception of people. But there is always the consumption--good aspect of human resource, in that an educated, healthy and gainfully employed person, by virtue of those attributes, is a more “complete” person. By being a “better” citizen, the externalities of HRD benefit the family, neighbours, communities, nations and humankind in general. A formal analysis by Lazear[v] has revealed that the production and the consumption aspects of HRD are not easily separable and are, in fact, complementary. Hence, all aspects of HRD are contributory factors to development in general.Human resource is “core” in that it adds value to other resources. All material things are dependent on the human factor for purposes of generation (e. g. capital, equipment and finances), utilization (e. g. land and other natural resources) or organization (the essence of entrepreneurship). Resource valorisation and beneficiation cannot occur without the creativity of the human agency. Figure 1 captures the essence of this human resource core model. Interactions between the various strategic elements are shown here by dual arrows.

There is also the human capital theory pioneered by Gary Becker.[vi] According to this theory, people possess human energy and ability that constitute the wealth of a nation and which is a major source of competitive advantage.[vii] Human capital is a stock, a certain quantity at a given point in time, and can be increased or diminished by positive or negative flows, respectively. People invest time, energy and other resources in order to acquire knowledge, health and livelihood. In so doing, they expect some level of return on that investment. This return takes the form of compensation, self-actualisation and an enjoyable work environment. There is evidence of a high rate of return on investment in HRD, whether looked at from the point of view of the individual (private rate) or the society (social rate). Typically, this rate of return exceeds comparable rates of return in physical and financial assets.[viii]

Human energy and ability are latent energy which can be transformed into kinetic energy by people's behaviour which in turn is shaped by attitudes and pathos: “the relationship, the emotional alignment, the understanding that is taking place between people.”[ix] So, to become effective, human capital has to have a socio-cultural substructure of mutual trust, cooperation and other forms of social capital that show up in the relations between persons. A proper combination of human capital and social capital, i.e. human resources development, would ensure that other resources are tapped and that the resultant output is used effectively and efficiently. It could also serve as the conduit for financial intermediation and work ethic, among others.

It is very difficult to measure the social capital component of human resources, given its largely qualitative nature. It is capital of a cultural nature, culture being the whole complex of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features that characterise a society or social group. It includes not only arts and letters, but also modes of life, the fundamental rights of the human being, value systems, traditions and beliefs.[x]

Culture underpins “society’s institutions, its legal system, its processes of governance, legitimation, and participation, all that web of intricate links and transactions that define a society’s character as well as delimit its pattern of economic development.”[xi] Looked at in this way, human resource is human capital augmented by socio-cultural capital. Some of this cultural collectivity can be learned through formal and informal education processes. It “needs to be understood as a socially embedded and multi-dimensional phenomenon that takes time to reshape and to accumulate.”[xii]

As noted in the introduction, health is an important component of human resource and, in fact, healthy nations are also wealthy nations.[xiii] Both health and education are major determinants of human welfare and development which, according to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), is “the process of expanding people’s choices through their access to economic resources, and their ability to acquire knowledge and live a healthy and long life.”[xiv]

The goal of HRD initiatives should be to develop capacities that are needed to realize sustainable human development (SHD) a development which is pro-people, pro-jobs and pro-nature and is characterized by empowerment, cooperation, equity, sustainability and security.[xv] In this undertaking, “education is the first step [and] creating employment opportunities is the next”[xvi] because it “is the key to the new global economy…. It is central to development, social progress and human freedom.”[xvii] This primacy of education was emphasized by the UN Secretary General’s Millennium Report to the General Assembly.[xviii] In the same report is a synopsis of a 1999 world survey by Gallup International which found that “people everywhere valued good health and a happy family life more highly than anything else.”[xix] They also stressed jobs.[xx] The three phenomena: health, education and jobs, are covariant, with education being a main determinant of health status.[xxi] Indeed, a healthy educated population with employment opportunities raises productivity, and thus leads to growth and development.

In summary, human resources are crucial to the process of adding value to all other resources and in ensuring sustainable human development. Human beings are the agents and the beneficiaries of this development. Their capacity as agents of Sustainable Human Development ( SHD) can be formed, maintained and utilized. How Africa has fared in these areas is examined below.

Human Resource Formation

The demographic baseline is the size of the population estimated at around 766 million in 1999.[xxii] A good indicator of the level of education is adult literacy rate, defined by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as the percentage of people aged 15 and above who can read and write at least a simple statement on their everyday life in any language. A large proportion of this cohort is in the labour force. For a more complete picture, the adult literacy rate is supplemented by the gross enrolment rates, that is, the number of students enrolled at a level of education, regardless of age, as a percentage of official school-age population for the level, namely primary, secondary and tertiary levels of education. (Comparative statistics on adult literacy are given in table 1 below. These statistics cover a span of 15 years.)

| Country Groups | 1985 | 1990 | 1992 | 1995 | 1997 | 1998 | 2000 |

| SSA | 48 | 51 | 54 | 57 | 59 | 60 | 60 |

| LDC | 40 | 45 | 47 | 48 | 51 | 50 | 51 |

| All DC | 60 | 64 | 68 | 70 | 71 | 73 | 74 |

| World | 72 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 79 |

Notes: DC stands for Developing Countries; LDC stands for Least Developed Countries; and SSA stands for Sub-Saharan Africa.

Sources: UNDP, Human development report (various issues); World Bank, World development report (various issues); and UNESCO Website (August 2000).

The figures show that adult literacy rate in Africa has been rising over time, suggesting a rising trend in the stock of human resources. Compared to other regions of the world, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has, on the average, consistently outperformed all the other Least Developed Countries (LDCs); but lags behind the mean for all Developing Countries (DC). But two things should be noted. First, that the average rate of literacy in SSA is quite low, only 60 per cent of the adult population. Secondly, this average hides the large disparities that exist in the continent. In fact, the level of illiteracy stands at above the average for SSA in 21 of the 53 regional member countries of the African Development Bank Group.[xxiii] So, there is a huge backlog in human resource development in Africa.

Human Resource Maintenance

People have to provide for themselves or be enabled to provide themselves with food, clothes, health services, education, social amenities, transportation, employment opportunities, etc. These basic human needs and other discretionary supplies constitute a crucial element in the maintenance of human resources. Taken as a set, health status is greatly impacted by all of the other elements, health being the condition of being sound in body, mind and spirit, especially freedom from physical injury or pain.[xxiv] Measures of health include longevity (life expectancy at birth), crude death rate and infant mortality.Like is generally the case globally, the longevity of the female population is a little longer than that of the male population. For both sexes, life expectancy is improving slowly, from 40 years in 1960 to 48 years in 1998. During the same period infant mortality rate, that is offspring dying before being one year old, decreased significantly, from 165 in 1960 to 107 in 1998 per 1000 live births.

Table 2: Indicators of Health Development in Sub-Saharan Africa

| Year | 1960 | 1965 | 1970 | 1980 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1988 | 1990 | 1992 | 1995 | 1997 | 1998 |

| LE | 40 | 42 | 44 | 50 | 48 | 50 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 51 | 52 | 49 | 48 |

| CDR | 24 | 23 | 20 | 17 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 14 |

| IMR | 165 | 157 | 138 | 114 | 129 | 101 | 100 | 108 | 107 | 97 | 92 | 82 | 107 |

N.B.: LE stands for Life Expectancy at birth in years; CDR stands for Crude Death Rate per 1000 people; and IMR stands for Infant Mortality Rate per 1000 live births.

Sources: UNDP, Human Development Report; UNICEF, The State of the World's Children; and World Bank, World Development Report (various issues).

It is noteworthy that the trends in these measures are not uni-directional. Life expectancy, though going up on the average, experienced a peak of 52 in 1995 before declining to 48 in 1998. Similarly, infant mortality rate declined steadily for two decades between 1960 and 1980, but rose sharply in 1984 to 129. Subsequent decline gave a best performance of 92 per 1000 live births in 1995; but a reversal of this gain is the current trend.

The slowness of the increase of life expectancy can be explained by many factors including war, natural calamities, diseases and other problems such as those connected with access to safe drinking water and sanitation.

HIV/AIDS Pandemic

Among s these factors, death and debilitation induced by HIV/AIDS pose a daunting challenge. It is rapidly becoming the leading cause of mortality in Africa. According to UNAIDS, the disease has caused more victims than war and it is reducing life expectancy in Africa. [xxv]

By the end of 1999, an estimated 34.3 million people worldwide, 33 million adults and 1.3 million children younger than 15 years, were living with HIV/AIDS. More than 71 percent of these people (24.5 million) live in SSA, where about 8.6 percent of all adults aged 15 to 49 are HIV-infected. In 16 SSA countries, the prevalence of HIV infection among adults aged 15 to 49 exceeds 10 percent. It is there, too, where the epidemic is growing the fastest. Unprotected sex accounted for most of the 3.4 million new HIV infections estimated among adults in SSA countries in 1997. In addition, mother-to-child transmission resulted in some 530,000 infected children being born to mothers with HIV, around 90 percent of the world total.

The human and economic cost of AIDS is enormous. According to the documentation at the 11th International Conference on AIDS held in Lusaka, Zambia,[xxvi] AIDS is the principal cause of the slow growth noticed in 10 African countries, due to the production loss arising from the increased rate of work absenteeism and the loss of qualified labour force. The performance of the almost non-existent social security in Africa will decline more and more because of the loss of funds related to the active population most stricken by the disease. In the informal sector, workers have to stop or shorten their hours of work in order to take care of their sick relatives.

Malaria

The other scourge impacting negatively on Africa's HRD is malaria. See box 1.

Box 1: The Impact of Malaria

Malaria kills more than one million people a year worldwide, with nine out of ten cases being in Africa. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that up to 30% of the 960,000 people who die of malaria every year in Africa are from countries affected by serious [ethnic] conflict, war or natural disaster ... Malaria slows down economic growth in Africa by up to 1.3% each year. The short-term benefits of malaria control can reasonably be estimated at between $3 billion and $12 billion per year. Yet presently only 2% of African children are protected at night with a treated bed-net.

Source: WHO Press Release, No. 28 (25 April 2000); 46 (30 June 2000); and 48 (5 July 2000).

Other Health Challenges

Here we briefly highlight three of them. The first is tuberculosis (TB), an infectious disease which claims 1.5 million new victims and kills almost 600,000 persons in Africa annually[xxvii]. In many countries, the number of cases of tuberculosis has doubled in the last five years, mainly because of the TB/HIV conjunction. TB is the major cause of death among patients with HIV in Africa. Even the handling of TB, pure and simple, is constrained by the inefficiency of health care systems, the contagious nature of the disease and the risk of resistance to drugs.

The second is malnutrition that makes individuals, particularly children, most vulnerable to diseases and other health problems. It causes death among children and may mentally or physically disable surviving persons. Insufficiency in micro-nutriments (vitamin A, iodine, iron, etc.) is common in Africa. Almost 30% of children under 5 years old suffer from malnutrition. Women tend to suffer more from lack of iron. More than 30% of pregnant women often have anaemia. The lack of iron increases death risk for delivering women and lowers the child capacity to work at school.

The third is diarrhoeal illnesses, such as cholera, typhoid and amoebic dysentery, that have been killing millions of people (mostly children) each year in Africa. This arises mainly due to poor hygiene and quality of sanitation. Usage of untreated water and lack of adequate wastewater disposal is widespread in both rural areas and many urban centres. The low allocation to social services and infrastructure during the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) era did not help matters.

Brain Drain

Another factor that erodes HRD is brain drain (see box 2).

Box 2: Human Resources Flight from Africa

“There has been an amazing brain drain from Africa. The rest of the world has benefited from this.” [xxviii] Data on the extent of the flight of the most educated Africans from the continent is provided by census data from industrialised countries. In the UK, there are 134,500 Africans: 14,500 have first degrees and 4,600 have advanced degrees. It has been estimated that “about 100,000 foreign experts work in Africa, whilst some 100,000 skilled Africans work in Europe and North America”.[xxix] These skilled Africans are typically doctors, research scientists and university teachers. Such an exchange of labour has positive aspects, but in general the emigration of many of highly educated from Africa is of concern given the scarcity of such people in the continent. Although governments pay for most of the cost of higher education, the emigration of graduates means that their countries do not benefit from these investments. Often these graduates are replaced by hiring of expatriates at great cost…).

Source: S. Appleton and F. Teal, “Human capital and economic development.” ADB economic research papers, no. 39 (1998).

Human Resource Utilization

One way human resources are formed and maintained is by being gainfully employed in situations that enable people to get their livelihoods by producing goods, services, and incomes. An indicator of this involvement is the labour force participation rate, that is, the proportion of the working age population which is active in the labour market. From table 3 it can be seen that the participation rate has been virtually constant for both men and women, although it is consistently higher for men relative to women.A look at the sectoral distribution of the labour force, reveals that the majority of the people are engaged in agricultural activities, followed by the provision of services and industrial production, in that order. This has been the case throughout the period covered by the data (1980-1996). But the trends are towards a decline in the share of agriculture and a rise in the shares of both services and industry in the labour force over time. This is in keeping with findings elsewhere as has been documented in studies using historical statistics.[xxx] The structure of the economy and its likely structural transformation should be factored into human resources development in order to meaningfully handle these issues.

Table 3: Labour Force Activity Rates in Africa (%)

| Indicator | Strata | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1994 | 1996 |

| Participation Rates | Male | 53 | 51 | |||

| Female | 37 | 36 | ||||

| Average | 45 | 44 | 44 | |||

| Sectoral Shares | Agriculture | 70 | 67 | 65 | 62 | |

| Industry | 11 | 12 | 13 | 15 | ||

| Services | 19 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

Source: ADB, African development report 2000, pp. 227 & 228.

In addition to the labour force participation rate being low, as documented in table 3, there is a high level of unemployment.

The unemployment rate is defined as the proportion of persons of working age who are not in paid employment or in self-employment. The general trend has been an increase in the employment rate since the 1980s. In recent years, the unemployment rate has ranged from around 10 per cent in the cases of Senegal and Tanzania to over 50 percent in the case of Nigeria and Angola. This situation has serious adverse consequences for human resource development:

Just as there is “learning-by-doing”, there is the obverse process of ‘unlearning by not doing’. Prolonged unemployment has purely economic costs in the form of depreciation and even disinvestment of human capacity through loss of skill due to lack of practice. Unutilized human resources, like idle productive capital equipment, represent excess capacity, and are thus wasted. Both human and physical capital are costly to accumulate, and should be put to work.[xxxi]

This raises the issue of allocative efficiency, which is compounded by the small size and imperfection of markets, and the constraints facing individual firms, such as high risk and poor infrastructure, which raise the cost of doing business in Africa. It also raises the issue of capital-labour substitution and the related concern of the employment content of growth. In general, the more the economic growth, the more employment is generated. This is because the more people are employed the greater will be the output.

Conclusion

This article has highlighted the past experience and the present situation in the countries of Africa ‘s human resources with regard to the achievement in the areas of education, health, and labour market. It has reviewed the important consensus about the major problems associated with human resources development in Africa, and their link with sustainable human development. It has also examined the gender aspects of HRD, disclosed the known aspirations and ideals, and suggested strategies to edge towards those ideals.

[ii] See, for example, G. A. Cornia, R. Jolly and F. Stewart (Eds.), Adjustment with a Human Face, Vol. 1: Protecting the Vulnerable and Promoting Growth (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987).

[iii] See UNRISD, Visible Hands: Taking Responsibility for Social Development (Geneva: UNRISD, 2000).

[iv] This is the title of his book published by Princeton University Press in 1998.

[v] See Edward P. Lazear, Allocation of Income Within the Household (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988).

[vi] Gary Stanley Becker, Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. With Special Reference to Education (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993).

[vii] See Ray Marshall and Mark Tucker, Thinking of a Living: Education and the Wealth of Nations (New York: Basic Books, 1993).

[viii] See, for example, T. Paul Schultz, “Formation of Human Capital and the Economic Development of Africa: Returns to Health and Schooling Investments”. ADB Economic Research Papers, No. 37 (1997).

[ix] Stephen R. Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Families (London: Simon & Schuster, 1999), p. 343.

[x] This is the definition given by UNESCO. See Ismail Serageldin and June Taboroff, eds., Culture and Development in Africa (Washington, D. C.: The World Bank. 1992, p. 4.

[xi] Loc. cit.

[xii] Louis Putterman, “Social Capital and Development Capacity: The Example of Rural Tanzania”, Development Policy Review, Vol. 13 (1995), p. 17-18.

[xiii] For an empirical causal relationship between health and wealth, see Lant Pritchet and Lawrence H. Summers, "Wealthier is Healthier", Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 30, No. 4 (1996), p..841-868.

[xiv] UNDP, Human Development Report (New York, 1990), p.10.

[xv] For parallelism, see UNDP, Reconceptualizing Governance, Management Development and Governance Division. Discussion Paper 2 (January 1997), p. 1-8, passim.

[xvi] UN, We the People: The UN in the 21st Century (New York, 2000), p. 15.

[xvii] Ibid., p. 14.

[xviii] New York, September 2000.

[xix] Ibid., p. 16.

[xx] Loc. cit.

[xxi] See Germano Mwabu, “Health Development in Africa”, African Development Bank (ADB) Group Economic Research Papers No. 38 (ADB Website, 2000).

[xxii] ADB, African Development Report 2000 (New York: Oxford University Press), p.213.

[xxiii] ADB, loc. cit.

[xxiv] Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (1989), p.558.

[xxv] UNAIDS Website, August 2000.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] ADB, African Development Report, 1998.

[xxviii] E. V. K. Jaycox, "Capacity Building: The Missing Link in African Development", The Courier, No. 141 (September-October, 1993), p. 73.

[xxix] J. Williams, "Primary Schooling for Girls", International Herald Tribune (15th June 1994).

[xxx] See, for example, the classic work of Simon Kuznets, Economic Growth and Structure (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983), passim.

[xxxi] L. P. Mureithi, "Labour Utilization and the Employment Problem in Africa", Chapter 6 in P. Ndegwa, L. P. Mureithi and R. H. Green (Eds.), Development Options for Africa in the 1980s and Beyond (Nairobi: Oxford University Press, 1985), p.73.