Farid James Omar: A Portrait of Typical Nuba Resilience

Emerson’s words fittingly describe Farid James Omar, a boy from the Nuba Mountains who lost his parents, escaped slavery in his own country and now seeks to find his dreams in a foreign country.

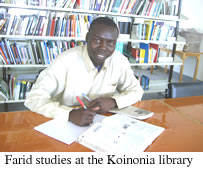

Farid narrates his haunting story unflinchingly. Despite his pensive disposition, his natural calmness perfectly conceals any traces of the painful past he suffered before finding his way to Nairobi, where he has become a star student at St Elizabeth Boys High School in the affluent Karen suburb.

Farid narrates his haunting story unflinchingly. Despite his pensive disposition, his natural calmness perfectly conceals any traces of the painful past he suffered before finding his way to Nairobi, where he has become a star student at St Elizabeth Boys High School in the affluent Karen suburb.

Farid was born in 1986, the second youngest of six children, to a modest Christian family that lived in Abri, a small town in the Nuba Mountains of Central Sudan. His father tilled a small piece of land on which the family subsisted while his mother was a homemaker. Farid’s parents struggled with life and managed to provide their children with food, clothes and a steady roof over their heads. However, their measly means prevented them from sending all their children to school.

“Only two of my older brothers attended a nearby Arabic School,” Farid explains, “The rest of us stayed at home because our parents could not afford our school fees.”

When Farid was six, his father fell sick and died, thrusting the entire burden of providing for the family into the hands of his unprepared widow. Then three years later, tragedy struck again when government forces ostensibly battling the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) insurgency descended on Abri.

The soldiers stormed the little town, shooting indiscriminately, burning houses and seizing children and women for enslavement. They burst into Farid’s home and found him working with his mother in the farm. His mother was shot in cold blood, and before he could take in the shock, they seized him and dragged him away as his mother lay lifeless in a pool of blood.

Dozens of other children and women had also been captured from the area. The soldiers tied them all up and forced them to march towards an unknown destination. The journey was difficult and tiring, blistering the captives’ feet, but the soldiers brutality forced them to shamble onwards.

“We got bruises and swellings from the beatings we received along the way,” Farid recalls impassively.

After trekking for two days, the captives were delivered to a military camp at a place called Dalami. At the camp, they found scores of prior captives and were inducted into doing menial work for the soldiers. Everyday, they were woken up well before dawn, and worked continuously from the chilly morning right into the night – sweeping, cooking, cleaning, fetching water and collecting firewood among other chores. Any semblance of fatigue invited punishment. Even illness was treated as an excuse to shirk work. In fact, a sick captive would be beaten and forced to work regardless.

For the first two days, Farid could not bring himself to eat anything. The harsh conditions at the camp only made his inner grief more unbearable as his mind kept pondering over how his life had changed so suddenly. He was haunted by memories of the happier days before his parents died, and he wondered how his siblings were coping.

After one month at the camp, the thoughts became too depressing and Farid decided to escape.

“I knew it was very risky and I could be killed if caught, but my mind was made up,” he says.

One night as it rained heavily and everyone was asleep, Farid crept out of bed and slipped past the door into the darkness outside. Luckily, the heavy downpour made it difficult for the sentries to see him. He walked stealthily in the pitch blackness, then broke into a run as soon as the camp lay a reasonable distance behind him.

Tracing the road to Abri with difficulty, Farid trudged his way on for two days and spent two nights in the cold with thirst, hunger and fatigue as his only companions. He eventually arrived home, but what he found was devastating.

The home was deserted and the family house had been burnt down. A villager who had survived the attack told him his brothers and sisters had been offered shelter “up in the mountains” by a local church. The sympathetic villager took Farid to them, and they had an emotional reunion.

The church took care of them and helped them build a new house, following which they moved back into the family home.

Farid’s eldest brother took charge of the family, but just like his parents, he could not afford to send the younger children to school. Fortunately, a cousin who had spent over ten years fighting for the SPLA returned from the South in 1997. Having found employment with a human rights organization, he offered to accommodate Farid and his younger brother in his house and enrolled them at a “bush” school in Tabari.

The school was however ill equipped as there were no books, pens or pencils for the pupils, who sat on stones and attended their classes under trees.

Farid remembers the challenge very clearly.

“We wrote on any material we could lay our hands on,” he says, “Old newspapers, envelopes, anything. In fact, sometimes we just wrote on the ground with sticks.”

The teachers themselves were mostly local volunteers with minimal formal schooling. However, they made sure their pupils learnt that education was a sure passage to a better life. This message became indelibly etched in young Farid’s mind. It drove him to study hard, knowing that education could open doors to a bright future that could possibly insulate him from the horrors of his dark past. In due time, he became one of the best students at Tabari.

In the year 2000, Koinonia was asked to find two former Nuba slaves who could narrate their experience and send them to Italy. In the process of this search, Farid and an even younger child, Yoannes, were identified as former slaves. It was however deemed that having the two children narrate their ordeal in Italy could stress them further, and they were instead offered educational support.

Since the Koinonia schools in the Nuba Mountains were not yet in existence, Farid and Yoannes were airlifted to Nairobi, where they were welcomed by Father Renato “Kizito” Sesana and placed into Koinonia’s Anita Home. Later on, they were moved to the Koinonia House at Riruta Satellite, Nairobi.

“Settling down was initially very difficult,” Farid says, looking back to his first days in Nairobi. He did not speak any Kenyan language and was yet to accustom to his strange new life so many miles away from home.

However, he was lucky to meet Paulino, an old friend who had come to Anita Home much earlier. Having known Paulino from way back in the Nuba Mountains, Farid found the courage to toddle through the initial motions of his new life. Pretty soon, he acquired a smattering of Kiswahili and started making new friends.

Farid and the other two Nuba boys were put through informal tuition to prepare them for school enrolment. In January 2001, they sat for their placement interviews. Farid did very well and was enrolled at the elite St. Elizabeth Boys Primary School in Karen.

“It felt amazing to put on my new uniform and be allocated a real desk in a real classroom,” he later wrote in an essay.

In 2005, Farid sat for his final primary school examinations. He passed well and was admitted to his old school’s secondary section. He is now in Form Three, and is set to graduate from high school next year (2009). In the last school term, he emerged the top student in his class with a mean grade B+. In the meantime he requested to be enrolled into catechism classes and was baptised James.

When asked what motivates him to do so well in his studies, Farid pauses for a moment, then lifts his eyes to respond.

“My late parents could not afford to take me to school,” he says reflectively, “I longed for this kind of opportunity, and from the day I arrived at St. Elizabeth’s, my ambitions soared.”

“I would like to become one of the world’s best heart surgeons,” he adds. “If I succeed, I hope to return to the Nuba Mountains and help save lives there. There aren’t many doctors in Nuba, and many people, including my father, have died for lack of proper health care.”

Farid has a lot of reverence for Father Kizito and Gian Marco, the president of AMANI. He also feels greatly indebted to AMANI and Koinonia for having helped him attend school in Kenya, and inspired by Father Kizito’s humanitarian work, hopes that he too will one day help foster a better life for his fellow Nuba.

“My longtime aspiration is to set up a well equipped hospital and construct a good school in the Nuba Mountains,” he says.